NAS

You want a NAS device that is repairable, non-proprietary, reliable, energy efficient, cost efficient, and standalone.

I won't tell you why you want this. If you're reading this post, you've probably already decided that you want one, but don't know what you should build. This guide is written around building a device for home use. It reflects decades of experience, but is written to reflect reality at the time the document was written. If you are reading this post ten years into the future, the specific information about hardware and software may no longer apply, but the reasoning that chose the hardware and software in the first place is unlikely to go out of date any time soon (and has remained mostly consistent for the previous twenty years at least!).

Repairability

It's important that the device be repairable. There are lots of different aspects that affect repairability, but I think the most important are:

- The device is made from commodity parts that are, themselves, not special in any way. You can always get replacement parts cheaply.

- The software running on the device is aimed at the computer literate, and therefore when something goes wrong, the software actually tells you what went wrong rather than infantilizing you with messages such as "Oops, something went wrong!".

- You have built the device yourself from parts, and so the internal construction is not a surprise and you're not dealing with anything that was designed to prevent you from opening it.

Non-Proprietary

It's critical that the device be non-proprietary. This ties into all of the other requirements here.

- Companies producing non-standard, proprietary hardware are not incentivized to make that hardware reliable. After all, they want you to discard the current hardware as quickly as possible and buy the next one.

- Companies producing proprietary software are incentivized to lock-in consumers. This harms repairability because it leads to systems that are ossified around a particular piece of software because, for example, the vendor abandoned the software and now the user cannot get their data out of it, and cannot replace it.

- Companies are incentivized to enshittify. This harms reliability because you can never trust that what works today will still work tomorrow.

- Companies are incentivized to spy, and in some cases, to act upon the collected information in hostile ways. Consider, for example, DRM and anti-cheat systems that simply disable access to software if they don't agree with what is present on your computer.

We can avoid proprietary software easily. We cannot avoid proprietary hardware so easily: We have, unfortunately, regressed as a society to the point that electrical schematics are no longer provided with computer hardware. The best we can do is use hardware that conforms to various published open standards and can therefore be freely interchanged with other conformant hardware.

Reliability

Needless to say, a device that's going to be running 24/7 that is intended for long-term storage of data must be reliable. It must continue to work day after day, and require minimal maintenance. The system must guarantee the integrity of the data we store: Every single byte of data we store must be verifiably free of corruption for the entire lifetime of the device.

We'll aim for a lifespan of around twenty years. We must accept that hardware failures do happen, and build in a level of redundancy that matches our tolerance for failures (and build cost).

Energy Efficiency

As the device is running 24/7, we want energy usage to be as low as we can reasonably get it. However, if lowering energy usage requires using strange or non-standard/non-commodity parts, we'll instead use the commodity parts and live with a slightly higher energy usage.

Cost Efficiency

As this is a home NAS and won't be used as some kind of mission-critical business server, we don't want to spend obscene amounts of money on it.

Standalone

You may not be the kind of questionable individual who has a 19" server rack in their home, and nor should you need to be. If you are that kind of individual, you've probably already built something more advanced than the system we'll build here.

As this is a home NAS, we'll try to build something that doesn't require much of anything in terms of other hardware running on the network.

Non-Requirements

There are some goals that we deliberately won't try to achieve.

Expandability

It's possible to build a NAS where you can keep adding more storage over time. However, in my experience, it is better to:

- Work out how much storage you need for your existing data right now.

- Get some idea as to how much your storage usage is increasing daily, weekly, monthly...

- Linearly extrapolate out around ten years to get some idea as to how much storage you would need if growth continued at the present rate.

- Build exactly that system.

Why do things this way? Firstly, storage technology improves quickly. The amount of storage per unit of currency you can buy today increases year by year. This means storage is essentially deflationary; tomorrow is generally always a better time to buy storage than today. Keeping this in mind, you might as well take the simpler option: Buy the minimum that you need right now and that you know will last you for a good long while, and plan to build a successor system ten or twenty years from now that will massively increase your storage capacity (and energy efficiency, if trends continue). When you build the successor, you can copy your old data to the new system, switch everything over to the new system, and then turn off the old system, without service disruption. Because we're taking care to ensure that everything is very generic, commodity, and non-proprietary, migrating the entirety of your data to the new system can be done in one single command.

Secondly, we'll be using software filesystems that are drastically easier to manage if you are working with arrays of drives where all of the individual drives are the of same size. At some point in the past, it was economical to buy 1TB hard drives. It is now no longer economical to buy drives smaller than 4TB. This means that, at some point in the future, drive sizes we consider commonplace now may not even be purchasable later. Pick a size that makes sense right now and buy an array of those. Management simplicity is not to be undervalued!

Compute

We'll build a system that can run a few services (such as, perhaps, immich for a photo gallery), but we'll largely treat the system as being a dumb container for data, and that won't have a lot of CPU power or performance.

If you want to run lots of extra services, it's better to set up a separate machine specifically for those services. It's outside of the scope of this document, but you can make your storage accessible from the machine we'll build to other machines on your network.

Plan Outline

Here's the general approach we'll take for the hardware:

- We'll use ordinary x86_64 hardware.

- We'll use AMD CPUs.

- We'll use ASUS motherboards.

- We'll use Seasonic power supplies.

- We'll use Silverstone cases.

- We'll use 64gb of non-ECC memory.

- We'll use a PCI host bus adapter to get better drive connectivity than what will be on the motherboard.

- We'll use an array of non-SSD hard drives.

- We'll use a consumer-grade uninterruptible power supply to protect the machine.

For software:

- We'll run a conservative distribution of Linux that's focused on stability and long-term software support.

- We'll store data on ZFS.

Rationale

x86_64

x86_64 is the current de-facto standard architecture for servers and desktops.

Everything from the instruction set to the boot process is standardized and documented in

publicly-available documents. Machines built twenty years ago still largely

boot and operate the same way as machines built today. This is, sadly, at the

time of writing not the case for any other hardware architecture. In ten years

time, this may no longer be true, but it is true as of late 2025.

Additionally, x86_64 hardware almost inevitably involves

ATX

form factors, and so we will never have to struggle to find a computer case

into which our components will fit, and will never have to locate a power

supply with a non-standard connector.

AMD CPUs

AMD CPUs appear to be more cost effective than the competition and, importantly, AMD rarely releases new incompatible CPU socket types. This means that it is possible to buy compatible motherboards for many years beyond the release of each CPU.

ASUS Motherboard

In my experience, ASUS motherboards seem to use the most robust components and appear to have the best quality assurance. I have seen one ASUS motherboard fail in around twenty five years of purchases and deployments.

Seasonic PSUs

I have never seen a Seasonic power supply fail, and have never met anyone who has seen one fail. I have seen plenty of supplies fail from just about every other PSU vendor.

Update (2025-11-22): I'm defining "fail" here as "the power supply ran for some time and then stopped working". I have never seen a Seasonic power supply do this. I have had one Seasonic PSU show up with a broken fan, but I think this may have been damaged in shipping.

Silverstone Cases

Silverstone have a range of non-rackmount cases that have hot-swappable drive bays for home NAS applications. Once you have used hot-swappable bays, you never want to go back to having to open a case to remove drives.

Non-ECC Memory

I remain unconvinced of the utility of ECC specifically for home use. Cosmic rays absolutely do flip bits in memory, and this is a real problem, but statistically this is incredibly unlikely to cause actual practical problems for a single device in the home. In a data center with hundreds of thousands of machines with terabytes of memory per node, ECC is justified. Supporting ECC memory would require buying much more expensive hardware, so we just won't.

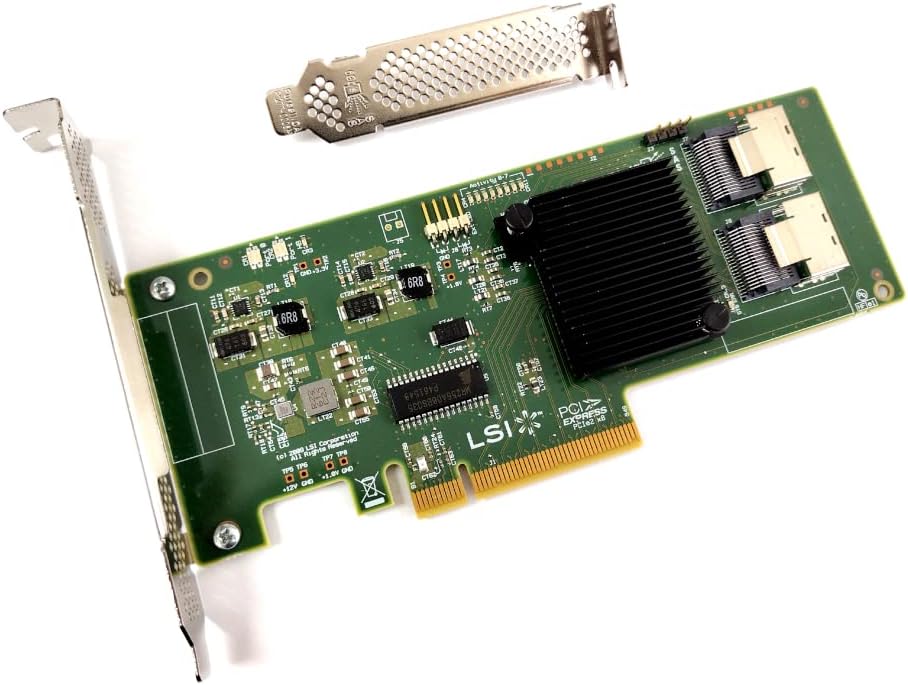

PCI Host Bus Adapters

Most cases that have hot-swappable drive bays will use

SAS connectors

(specifically SFF-8087). This is not a connector that most consumer

hardware users will ever see as it tends to only appear on server-class

hardware.

In order to connect these drive bays to a consumer motherboard, we need a host bus adapter card. These tend to look like this:

Note the two SFF-8087 connectors on the right hand side of the card. We

can connect two SAS cables from those connectors to the drive bays and

give ourselves (typically) eight drive connections. Additionally, this

can lead to big performance increases because drive I/O is performed over the

PCI bus instead of the motherboard's SATA hardware.

There is a thriving market in refurbished cast-off enterprise hardware. These cards can be found on eBay and Amazon for £20-£80. For our purposes, it almost doesn't matter which specific card we choose because they will all be sufficient.

Non-SSD Hard Disks

At the time of writing, purely in terms of price-per-terabyte, traditional "spinning rust" hard drives are still far ahead of solid state storage. For our purposes, we don't care about performance, we care about our storage being large and cheap.

Additionally, whilst solid state storage is still considered to be more reliable than traditional hard drives, the failure modes tend to be less desirable. In my experience, when solid state drives fail, they simply go from working perfectly to completely dead with no prior warning. Whilst traditional hard drives may fail more often, they tend to fail gracefully and let you know ahead of time that they're in the process of dying.

We'll use a single solid state drive to boot the operating system, but we'll use magnetic drives for our actual storage. We'll mitigate reliability concerns with redundant drives.

UPS

Computers generally don't like being subjected to voltage spikes or voltage drops. Magnetic drives, despite being vastly more robust nowadays, generally don't like having their electrical supply abruptly removed.

A common desktop uninterruptible power supply should be used to clean the supply of power to the computer, and to give you a good ten minutes to manually shut the computer down if your power goes out completely.

Linux

We'll use Linux because it's ubiquitous and vendor-neutral, and we'll stick to very boring and stability-focused distributions of Linux. Because we are using very generic and commodity hardware, and because we don't need the latest sparkly features, we don't need to use a Linux distribution that represents the bleeding edge of Linux development. We want reliable, stable, and boring.

We could use a NAS-focused distribution such as TrueNAS, but that would be tying our system to the fate of one company, and would make the software we're running less common and less "standard". Typically, anyone familiar with Linux can sit down at any Debian or RHEL system and be competent enough to diagnose and fix issues. For the kind of long-term support we need, RHEL, in particular, guarantees ten years of software support for each release.

My current choice for these kinds of systems is AlmaLinux (a 100%-compatible RHEL derivative), but Debian Stable is also a good choice.

ZFS

There is simply no other filesystem, at the time of writing, that even comes close to competing with ZFS in terms of reliability, data integrity, and administrative ease. ZFS is widely supported on multiple operating systems, and is used in everything from small deployments to truly huge supercomputer deployments at places such as Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

Critically, ZFS contains integrity features that transparently detect and automatically correct data corruption. It is the only filesystem that I trust for the long-term storage of data.

One small issue can arise with ZFS depending on which Linux distribution you're using. ZFS is completely open-source, non-proprietary, and is considered "free software". The source code is, however, distributed under a license that is considered incompatible with the license used for the Linux kernel. Therefore, ZFS is maintained outside of the Linux kernel project. Why is this an issue? Because ZFS is maintained externally, it inevitably slightly lags behind the current Linux kernel. Therefore, if you're using a very bleeding-edge Linux kernel, there's always a chance that ZFS won't (yet) be compatible with it. You can reboot the system after an upgrade and find that you can't load your ZFS filesystems. This makes unattended upgrades something that you just can't have. This problem goes away entirely if you are using a stability-focused distribution.

Disks

This is the part of the build that I can't be too specific about because the actual numbers involved will be based on your needs. As mentioned, you'll need to work out what your ten year storage requirements are and buy accordingly. I have a post from last year that examines drive pricing. You also need to decide how tolerant the system must be to drive failures.

Failures

Ultimately, systems like ZFS (and the hardware-based RAID systems that preceded it) aim to do one main thing: Take a set of drives, and present the illusion that they're really one large drive. Additional concerns include "spread all the drive I/O over all drives so that we can read and write data much more quickly than we could if we had a single drive as the bottleneck" and "make it so that if one or more drives fail, we can replace them and carry on without losing data".

Disks inevitably fail. A filesystem such as ZFS, depending on how it is configured, is capable of continuing to run without interruption even when drives fail. The main choice you must make when planning an array of drives is "how many drives must fail simultaneously for data loss to occur?"

ZFS takes drives and combines them into a storage pool. We have the freedom to decide exactly how the drives are combined, and the choices we make change how the storage pool performs, and how much failure it can tolerate before breaking down. Depending on how we choose to configure things, we are essentially betting against the probability of a specific set of failure conditions occurring. We can increase the safety of the system, and this will generally require us to trade against performance, or trade against the total usable storage size of the pool.

Let's assume, for the sake of example, that we have six drives. The most commonly seen configurations for storage pools of six drives include...

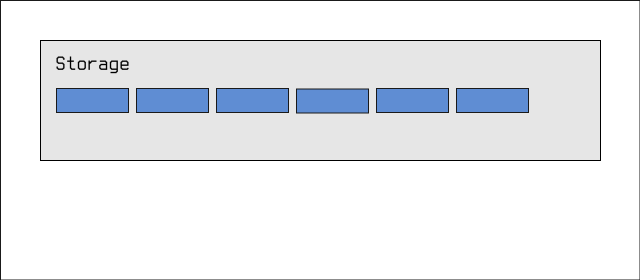

Fast And Dangerous (Striping)

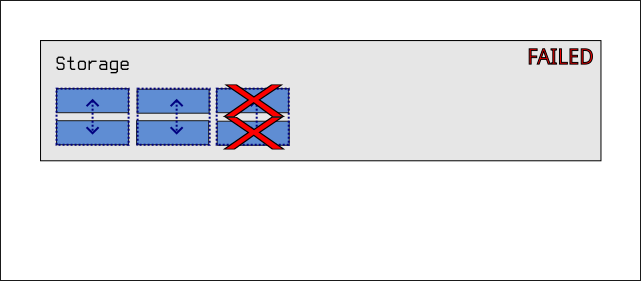

The simplest and most dangerous configuration is known as striping in traditional RAID terminology:

We have a storage pool called Storage, and inside that pool we have

six drives. Any data written to the pool is distributed amongst the six

drives. This gives us very high write performance; the underlying system

can write data to any drive that's ready to receive it, essentially multiplying

our effective bandwidth by 6x. Additionally, we get to use every single byte of

every drive for our storage. This means that if we bought 36TB of storage, we

get to use all 36TB for our data.

Unfortunately, this comes at a cost. If one single drive fails, we lose all of the data in the pool.

Obviously, for long-term data storage, this kind of configuration isn't suitable. This kind of setup might be used in situations where we care about performance above all else, or where the data is purely temporary and where we can completely destroy and create the storage pool anew.

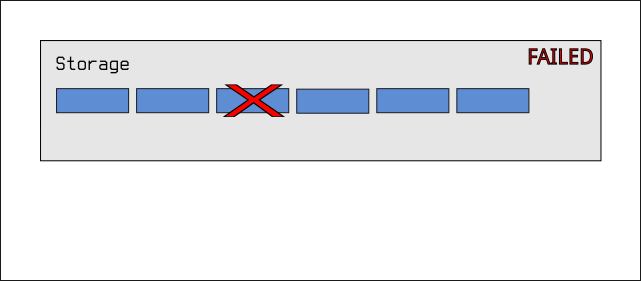

Mirroring

Another kind of pool configuration we could use involves mirroring:

We divide the six drives up into pairs of drives, and we join together each pair such that data written to one is automatically mirrored onto its partner. If one partner of a pair fails, there's no problem! The system can continue functioning. ZFS will tell you that the drive has failed, and will tell you that you need to replace it, but everything will continue working anyway. In fact, the system would keep working even if a partner from each pair failed:

In this particular configuration, you can see that we effectively spend half of our storage on redundancy. If our six drives add up to 36TB of space, we only get to use 18TB of that space for our data, as the other 18TB is spent on mirrored copies of data.

However, if a single pair fails, we are back to the same situation as pure striping: We lose all of the data in the pool.

This doesn't sound particularly good, but consider that hard drive failure rates are extremely low. Backblaze regularly publishes drive failure rates from their datacenters. Annualized failure rates for most drives are in the single digit percentages. Generally, if you have a hundred drives, you might see one or two fail per year. Consider also that we're not betting that two drives won't fail at the same time, we're actually betting that two specific drives in the same pair won't fail at the same time, which is much more unlikely.

It's also possible, if you have unlimited funds and an extreme aversion to risk, to create triplets or quadlets (and beyond) of drives so that three or four drives in the same group have to fail at the same time for there to be any data loss. I've never actually seen anyone do this as most people aren't willing to buy three or four times the storage that they need and spend it on redundancy.

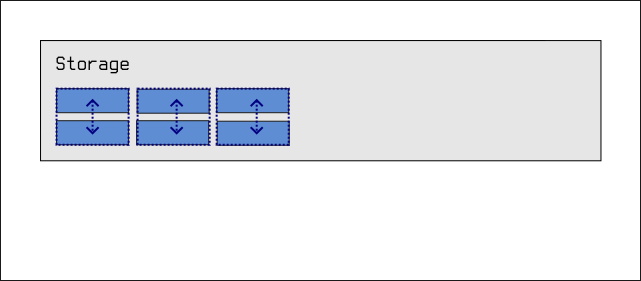

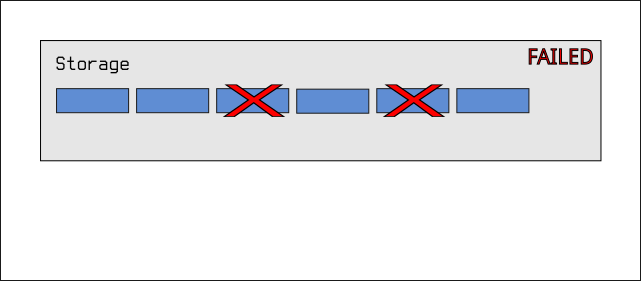

RAIDZ1, RAIDZ2, RAIDZ3...

The last configuration supported by ZFS falls somewhere between the above

two configurations in terms of safety, performance, and cost. We can configure

a storage pool in so-called raidz1 or raidz2 mode. In raidz1, one drive's

worth of storage space is used as "parity" data that can be used to recover

from the failure of one drive. This gives us a configuration that looks

somewhat like striping (although it doesn't have the same performance

characteristics), but the pool can tolerate the failure of any one drive

in the pool. A failed drive will simply degrade the pool, but the pool will

keep working. Replacing the failed drive will restore the pool to full

performance.

In a six drive array, this means we get to use (5 / 6) * 100 = ~83% of our

storage pool for our data, with one drive's worth of storage being used for

recovery. If any two drives fail simultaneously, the pool fails:

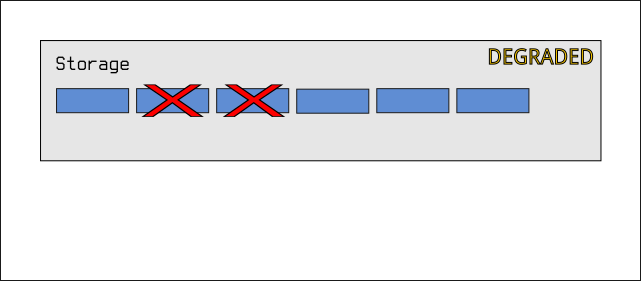

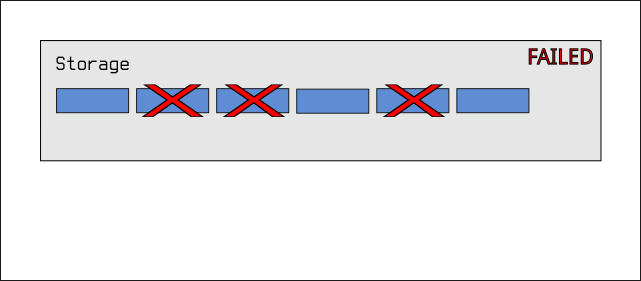

Accordingly, raidz2 simply uses two drives worth of storage for

recovery, and so the pool will only fail if any three drives fail

simultaneously:

This obviously allows use to use (4 / 6) * 100 = ~66% of our storage pool

for data, with two drive's worth of storage used for recovery.

Of course, raidz3 uses three disks worth of storage, and can tolerate

four disks failing...

For long-term data storage, I have tended to use raidz2. I feel it balances

safety with allowing me to use more than half of the storage that I paid for.

I feel that, I might get unlucky and have a second drive fail before I replace

the first one, but it seems very unlikely that I'd allow a third to fail. If

I had unlimited funds to throw at storage, I would use mirroring everywhere.

For small arrays of three drives, I use raidz1.

There are more complex configurations possible if you are using much larger numbers of drives, but that's not going to happen in a home NAS setup.

Manufacturers

Repeating some common wisdom here: When you buy drives, try to buy drives from a mix of manufacturers. This reduces the chances that you manage to buy two drives from a batch that had a manufacturing defect. If you do end up having to buy multiple drives from a single manufacturer (which you will if you're buying six or more drives), and you're using mirroring for pairs, try to ensure that each drive ends up in a different pair.

Drive Guidelines

I'd assume the following:

- Aim to buy either six or eight drives.

- Ensure all of the drives are the same size.

- Try to buy a mix of drives from different manufacturers.

- Do not buy drives smaller than 4TB; doing so is literally throwing money away.

- Aim to use

raidz2unless you have money to burn.

Shopping

We need a low end AMD-compatible ASUS motherboard with at least one PCI slot. We need space for an NVMe to boot the operating system. We need support for 64gb of RAM. We need a low-end AMD CPU that has an embedded GPU so that we don't have to use an external graphics card.

There are many components that would fulfill these requirements, but here's an example list pulled from Scan at the time of writing:

| Item | Price |

|---|---|

| ASUS ROG Strix B550-F | £149.99 |

| AMD Ryzen 3 3200g | £52.49 |

| 64gb Corsair RAM | £150.00 |

| 650w Seasonic PSU | £99.98 |

| 500gb WD NVMe | £47.99 |

| £500.45 |

Note: We are late in the lifecycle of DDR4 memory. If you are concerned about this, simply pick another low-end ASUS motherboard that takes an AM5 CPU with an embedded GPU instead, and use DDR5 memory and an appropriate low-end AMD Ryzen CPU instead.

We also need 6-8 drives that will vary depending on our storage needs. In 2024, 6x8TB drives cost around £1000. That price drops month-by-month, and the density of drives increases.

We also need a SAS host bus adapter card. eBay has piles of these. Most of the cards are refurbished cards from LSI. They are typically labelled along the lines of:

9300-8i SAS LSI HBA - IT Mode NAS Unraid ZFS TrueNAS Proxmox JBOD - NO BIOS LSI 9300-16i SAS HBA Card IT Mode NO BIOS Unraid ZFS TrueNAS Proxmox JBOD Server LSI 9300-8i SAS HBA Card - IT Mode NAS Unraid ZFS TrueNAS Proxmox JBOD - NO BIOS

Here's an example:

It is difficult to go wrong when buying these cards, but use your best judgement: The above examples make it clear that it is intended for use in some kind of home NAS (hence all the keywords such as TrueNAS, Proxmox, JBOD, ZFS, and etc). The cards will have been flashed with basic firmware that is essentially designed to offload all of the work to a software system such as ZFS.

Finally, a Silverstone case. Something like the CS383 is ideal for this kind of application. This particular case has SATA connectors in the drive bays, and so it will require a breakout cable to get from the SAS connectors on the PCI card to the SATA connectors on the drive bays. Other cases usually expose a backplane that has SAS connectors on it, so that will just require a standard SAS cable to get from the card to the backplane.

We should also use an uninterruptible power supply. I like Eaton power supplies, but they are not cheap. APC power supplies are tolerable, but they have introduced an anti-consumer practice of making it impossible to change the battery without voiding the warranty. It is entirely possible to change the battery, but you have to open the casing to do it. Eaton power supplies consistently give you a battery slot to make changing the battery trivial. The batteries are simple lead acid batteries and so will typically last over a decade. The computer we've described here will never draw more than 200W and will frequently be nowhere near this value. Any common uninterruptible power supply for desktop computers will "work".

Software

Get AlmaLinux or Debian Stable and install it onto the internal NVMe.

Then, follow the OpenZFS installation guide. It's typically a couple of commands to install the ZFS kernel modules.

A full guide to ZFS is outside of the scope of this documentation, but the existing manual is excellent, and there's a ton of information online on setting up storage pools. Once your pool is up and running, that's essentially the work completed. It's up to you how you decide to organize files in filesystems created in the pool.

You can copy files directly onto the machine using standard tools such as

ssh or sftp, or set up Samba to allow for backing

up over Windows file sharing.

Set up ZFS snapshots to

protect daily backups and allow you to efficiently go back in time to any

previous version of your data...

QR Codes

Print QR codes onto sticky labels that you can place onto the drawers of the drive bays. The QR code should contain the manufacturer, model number, and serial number of the drive that's in the bay. Then, when ZFS tells you that a drive has failed and you need to replace it, you know exactly which drive bay you need to open.

Frequently Ridiculed Questions

Why Don't I Just Buy A Proprietary NAS?

When it breaks, you can't fix it. It will come with a proprietary operating system. When it comes time to get your data off of it, you'll find you can't. The manufacturers will require the use of "certified" drives that just so happen to cost about four times as much as standard drives whilst being functionally identical. You are a helpless captive consumer and your data means nothing.

Why Don't I Just Back Up To The Cloud?

You'll pay a minimum of £4 per terabyte per month in perpetuity for the privilege of storing your data on someone else's computer. When it comes time for you to download or move that data, you'll pay for the privilege of doing that too. When their system is compromised, your data goes with it (which can be mitigated somewhat by end-to-end encryption). If the cloud provider goes out of business, or just decides that it can't be bothered to offer cloud storage anymore, your data is gone.

If you want to store around 36TB of data, that's £1728 per year. The hardware described here may well cost less than £1728 (depending on where you are in the world) and is a one-time fee (or perhaps once a decade), and you can access it as quickly as your LAN will allow for no cost.

I do recommend backing up some of your data to Hetzner Object Storage using rclone with end-to-end encryption as an extra off-site backup for peace of mind.

Why Don't I Store All My Data Offline In A Pile Of Disks?

Drives that are not powered up regularly tend to rot. A drive kept powered off in storage is not being checked for data corruption, and the corruption cannot be detected at a later date unless you've religiously stored checksums with all of your data. Corruption that is detected cannot be repaired. Flash cells degrade without regular supplies of power. Additionally, mechanical drives have parts that seize up over time when not used regularly. Your data may be in pristine condition on the drive, but that's poor consolation if the drive won't physically rotate anymore. Anything not actively managed succumbs to entropy.

Additionally: You should be taking daily backups. There is no excuse for not taking daily backups. If performing a backup daily takes anything more than typing the word "backup", you will simply not do daily backups. Having to take out and plug in a drive qualifies.

Having run FreeBSD for nearly two decades, I eventually got frustrated with it for various reasons and moved my workloads from "a lot of virtual machines on a FreeBSD bhyve host" to "a lot of OCI containers on a Linux host".

I try to run containers in as restricted and isolated a fashion as possible. Ultimately, I'm trying to limit the possible damage caused by a compromise of a single service. I've tried to take a layered approach starting from the kernel upwards. We don't have secure systems and probably never will, so all of my choices are based around making systems harder to exploit, and around limiting damage if and when something is compromised.

Distribution

I'm running containers on RHEL derivatives. There are multiple reasons for this:

-

The distributions have a very up-to-date

targetedSELinux policy that assigns each container a unique label. This severely limits what compromised container processes can actually do: Even if a container is completely compromised, the SELinux label effectively stops the container's processes from interacting with anything on the host system, and with any other containers. -

The distribution userland is compiled with a lot of exploit mitigation (stack protection, bounds-checked

libcfunction replacements, hardened allocators, read-only executable sections, control flow integrity, etc). This makes it harder for any vulnerable processes to be exploited successfully. There are distributions that enable even more hardening, but these often require building from source (Hardened Gentoo, etc) and nobody has time for that. -

The distribution kernel typically has most of the various kernel hardening features enabled. I'm told that Fedora is an early adopter of most of these features, and they percolate down into RHEL derivatives when it's determined that they aren't terrible. This makes it harder for kernel exploits to actually work.

-

The distribution kernel tends to exclude a lot of old drivers that don't have any place on modern "enterprise" hardware. Old drivers can be sources of vulnerabilities.

-

The distributions have an incredibly boring and slow release schedule with no incompatible changes between major releases. This keeps things stable. It also means that it's safe to run an automatic package updater (such as

dnf-automatic) to keep the host kernel up-to-date with the latest security patches.

I tried running CoreOS for a few years, but I found it too cumbersome. A one-line configuration file change requires a complete re-deploy of the entire virtual machine, and this can take 5-10 minutes depending on the VPS host. I understand what they're trying to do, but I just found it too annoying to work with in practice. Maybe if it was a lot faster...

I like Debian, but the lack of kernel hardening and the lack of a good container SELinux policy means that I've rejected it as a container host.

My requirement is that I want a userland and kernel that's hard to exploit.

Containers don't have their own virtualized kernels in the manner that bhyve

and other hypervisor guests do, so it's important to pick a kernel that's going

to be less subject to any local kernel exploits that might be launched inside

containers. RHEL derivatives seem to be about the best option that doesn't

involve paying someone to build custom kernels as their full-time job.

Podman

I'm running containers with podman. The set of different

ways one can run a podman container

could fill a book.

I've landed on the following set of configuration practices:

Rootful Containers

Containers can either be rootful (meaning the host's root user is the

user that starts the container) or rootless (meaning a non-root user on

the host starts the container).

I ran entirely rootless containers for over a year, with each container being run by different user on the host. This sounds like it should be optimal from a security perspective; if a container never had root privileges, then it presumably can't be the victim of privilege escalation.

Unfortunately, this turned out to be bad. Rootless containers are convenient for allowing users to run containers locally for development work and so on, but they're horrible for production use:

-

Linux container networking is already obscenely complicated, error-prone, and fragile. Couple this with the requirement to be able to set up container networking without root privileges, and it eventually becomes necessary to more or less implement an entire fake virtual network stack. They are, as far as I'm aware, already onto their third "userland network stack". It's exactly as complex and error-prone as it looks, and when it fails, it does so silently. With rootful containers, you can simply use

macvlannetworking, assign each container an IP address, and sidestep most of the horrible complexity. -

Convenient commands like

podman statsandpodman psonly show the containers from the current user (by design). If all of the containers are being executed by different users, then the utility of these commands is basically lost. With rootful containers, you can run these commands asrootand see all of the containers. -

Rootless containers actually end up somehow being less secure in many cases, because there are sandboxing features that require some privileges to be present in the first place in order to enable the features. In other words, a process needs to be slightly more privileged in order to be able to use sandboxing features to drop itself to a less privileged position than an ordinary unprivileged process. I'll cover this in a bit.

-

The actual storage for container images ends up being spread over all of the home directories of all of the "users" that run the containers. With rootful containers, image data ends up in

/var/lib/containers, and that's it.

I'm now exclusively running rootful containers and using a set of configuration options that result in containers that are, as far as I'm aware, as isolated from each other as possible, and as isolated from the host as possible.

read-only

This is the first blunt instrument in the box. When a container is run

with --read-only, it's not possible for processes inside the container to

write to anything in the filesystem except for in explicitly read/write mounted

volumes. This has the following benefits:

-

Containers become stateless (other than any explicit state in volumes that the admin provides).

-

Compromised processes can't overwrite system binaries inside the container. A compromised process attempting to replace

/usr/sbin/sshdwill find that it can't. -

It breaks any poorly designed images that run massive piles of setup scripts on startup that write all over the filesystem. This means you learn quite quickly that an image is incompetently packaged, and you can replace it with a better one.

I couple this with exclusively using --rm so that every time a

container is started, it's guaranteed to be starting from a pristine

"has never run before" state.

cap-drop all

On Linux, the root user is simply an ordinary user that happens to have

more capabilities

by default. When a podman container is run by the root user, podman

does automatically drop some capabilities that it knows containers should

never have.

When the --cap-drop all command-line option is used, all of the possible

capabilities are dropped, turning all of the processes inside the container

into utterly unprivileged processes. A user that appears to be root inside the

container won't be able to do any of the things the root user can usually do,

such as chown files it doesn't own, and etc.

security-opt=no-new-privileges

The Linux kernel has a no new privileges

flag that can be set for processes. This simply prevents any process from

gaining any new privileges via an execve() call. This is essentially

paranoia that I use in combination with --cap-drop all.

userns auto

On Linux, a user with ID 0 inside a container is equivalent to a user

with ID 0 outside of the container. This means that, should a process

running under user ID 0 somehow get access to parts of the host filesystem,

then it can read and write files that are owned by user ID 0 on the host.

It can also send signals to other processes that have user ID 0.

The --userns auto option eliminates this problem. Instead of the container's

processes running under the same ID of the user that started the container

(root), podman consults /etc/subuid and /etc/subgid and then picks

a random region of 65536 UID and GID values that are guaranteed not to

overlap with any on the host system, and guaranteed not to overlap with any

in any other container. /etc/subuid and /etc/subgid tend to look like this:

# cat /etc/subuid containers:2147483647:2147483647 # cat /etc/subgid containers:2147483647:2147483647

The first number is the starting UID/GID, and the second number is the number

of ID values that are permitted to be used. This essentially means that all

container processes will be assigned UID/GID values in the range

[2147483647, 4294967294].

For example, inside a container, nginx believes it is running as UID 0.

However, on the host system, we can see that it isn't:

# ps -eo uid:20,pid,cmd | grep nginx | grep master 2147479553 319065 nginx: master process nginx -p /nginx/ -c /nginx/etc/nginx.conf -e /nginx/var/error.log

It is actually running as UID 2147479553. The processes are also placed into

an isolated user namespace.

When I mentioned earlier that there are sandboxing features that require privileges in order to get to a less privileged position, this is what I was referring to.

Volume Z flag

As mentioned, each container on a RHEL derivative gets a unique label. The

SELinux policy is written such that volumes mounted in the container need to be

assigned the same label or the container processes won't be able to read or write

anything on the volume. The Z flag, when used on a volume, assigns a label

that's unique to the specific container being executed, whilst the z flag

assigns a label that can be used by all containers (if containers need to share

data via the filesystem). For example:

# podman run --volume /data/containers/example01/data:/data:rw,Z ...

If another container was compromised and somehow got access to

/data/containers/example01/data, it still wouldn't be able to actually read

or write anything there because the SELinux label wouldn't match.

If a volume doesn't have a Z or z flag, the containers simply won't be

able to read or write at all. It follows that, as the host system files and

processes won't have these labels, compromised containers have no ability to

read/write to locations on the host filesystem.

idmap

If containers need to share data via the filesystem, volumes can use the

idmap flag. This performs a bit of magic that allows files to have the same

UID/GID between different containers - something the --userns auto option

would normally specifically prevent. The idmap flag requires a compatible

filesystem (ZFS and XFS are good candidates) and also requires rootful

containers, and so is another instance of having to start out with extra

privileges in order to end up with fewer privileges.

seccomp

I don't apply any extra seccomp policies

because it's too much of a maintenance burden. I do want to point out that

podman applies its own restrictive seccomp policy to all containers by

default.

For example, containers are forbidden from calling any of the system calls that

are used to load kernel modules. This means that, even if you didn't apply any of

the other security mechanisms that are listed here, a process running as

root inside a container still wouldn't be quite as capable as a process

running as root on the host.

It also means that, if a particular system call has an exploitable bug in it, a process inside the container might not necessarily be able to make the call and exploit the bug.

Resource Limits

I run each container in its own systemd slice which, essentially, means that each container gets its own cgroup.

I only use CPU and memory accounting, and I tend to limit container resources on a somewhat trial-and-error basis. I use ZFS filesystem quotas, in combination with giving each container its own filesystem, to prevent runaway container processes from filling up disks.

I tend to set memory limits such that containers run at roughly 80% of their prescribed limits. For example:

ID NAME CPU % MEM USAGE / LIMIT MEM % 97c719b8ea55 objects02 0.56% 406MB / 512MB 79.30%

Containers that exceed limits are simply killed and restarted (and I have monitoring to indicate OOM conditions, and to notify me if a container is repeatedly restarting).

Frustratingly, there seems to be some kind of bug in podman, at the time

of writing, when running rootful containers. Sometimes resource limits are

not applied. For safety, I specify the limits redundantly in the

systemd unit

file for each container:

[Service] Slice=services-objects02.slice Restart=on-failure RestartSec=10s TimeoutStopSec=70 TimeoutStartSec=300 CPUAccounting=true CPUQuota=400% MemoryAccounting=true MemoryHigh=512000000 MemoryMax=512000000 [Container] ContainerName=objects02 PodmanArgs=--cpus=4 PodmanArgs=--memory=512000000b

This ensures that, if podman fails to apply resource limits, the systemd

service will still have those limits applied to the slice in which the

container is placed, and so it will still be subject to those limits.

Networking

I'm using macvlan. This seems to be the "simplest" option in terms of

moving parts; there's no NAT involved in the host kernel. You simply assign

each container its own IP address, and the container appears as if it was

a (real or virtual) machine on the LAN.

All Linux container networking schemes seem to have one or more fatal flaws

that make them unusable for one workload or another, but the macvlan scheme

seems to have the fewest of those, and is only available to rootful

containers.

All of the schemes that are available to rootless containers have nightmarish lists of caveats and horrible failure modes that can result in excruciating amounts of debugging just to work out why packets aren't getting from one place to another. In my opinion, life is too short to bother with them.

I run extremely restrictive default-deny firewall rules on all hosts, but I won't go into detail on that here because it's not specific to containers.

Summary

- I run containers that start out life as rootful containers, but drop all privileges to the point that they're less privileged than rootless containers.

- I run containers as random unique UID and GID values in isolated user namespaces.

- I run containers with all capabilities dropped, and with process flags that prevent any acquisitions of new capabilities.

- I run containers on read-only filesystems.

- I set strict resource limits to quickly kill runaway (maliciously, or accidentally) processes.

- I prevent containers from having access to the host or to each other with SELinux labels.

- I run containers on reasonably hardened kernels.

At the time of writing, I believe this is about as "secure" as is practically possible. The biggest weakness of the system is kernel-level exploits; if someone in a container successfully exploits the kernel locally, then none of the security features matter. This is, however, also true of virtual machines except that the compromised virtual machine has to take one step further and compromise the host kernel.

After a lot more back and forth with Bosch support, I finally got an actual answer.

The serial number on a Dremel is written on what they refer to as the "data plate" on the side of the tool. The number doesn't match what's in any of the QR codes on the tool, and it isn't labelled as being a serial number.

It's a 3-4 digit number, followed by a date of the form MM/YYYY.

If the first number was 179 and the date was 02/2024, then the serial

number of the tool would be, apparently, 0179022024.

I'm in the process of migrating io7m.com to Hetzner.

My previous setup on Vultr consisted of a single bastion host through which it was necessary to tunnel with ssh in order to log in to any of the multitude of servers sitting behind it.

This has downsides. Anything that wants to access private services on the hidden servers to perform monitoring, backups, etc, has to know about all the magic required to tunnel through the bastion host. When I first set up those servers, Wireguard didn't exist. However, clearly Wireguard now exists, and so I've incorporated it into the new arrangement on Hetzner instead of having to painfully tunnel SSH all over the place.

The goal is to essentially have the servers that sit behind the bastion host

appear as if they were ordinary hosts on my office LAN, whilst also not being

accessible from the world outside my LAN. This is achievable with Wireguard,

but, unfortunately, it requires a slightly complicated setup along with some

easy-to-forget bits of NAT and forwarding. In my case, at least one of the NAT

rules is only necessary because of what I assume is an undocumented

security feature of Hetzner private networks, and we'll get to that later.

There's also a bit of MTU unpleasantness

that isn't required if you aren't using PPPoE to access the internet.

I'm documenting the entire arrangement here so that I have at least a fighting chance of remembering how it works in six months time.

This is the basic arrangement:

On the left, workstation01 and backup01 are two machines in my office LAN

that want to be able to reach the otherwise unroutable server01 and server02

machines hosted on the Hetzner cloud. The router01 machine is, unsurprisingly,

the router for my office LAN, and router02 is the Hetzner-hosted bastion

host. All IP addresses here are fictional, but 70.0.0.1 is supposed to

represent the real publically-routable IPv4 address of router02, and the other

addresses indicated in blue are the private IPv4 addresses of the other

machines. My office LAN is assumed to cover 10.20.0.0/16, and the Hetzner

private network covers 10.10.0.0/16.

This is also intended to be a strictly one-way arrangement. Machines on my

office LAN should be able to connect to server01, server02, etc, but no

machine in the Hetzner private network will ever have any reason to connect

in to my office LAN.

Wireguard (router02)

The first step is to set up Wireguard in a "server" style configuration on

router02. The configuration file for Wireguard on router02 looks something

like this:

[Interface] Address = 10.10.0.3/32, 70.0.0.1 ListenPort = 51820 MTU = 1410 PrivateKey = ... [Peer] # Router01 AllowedIPs = 10.10.100.1/32 PreSharedKey = ... PublicKey = ...

This configuration specifies that Wireguard listens on UDP port 51820 on

10.10.0.3 and 70.0.0.1 for incoming peers. The first strange thing in

this configuration is that we only define one peer and specify that its allowed

IP address is 10.10.100.1. Packets with a source address of anything else will

be discarded. This address doesn't match the address of anything on the office

LAN, so why are we doing this? This brings us to...

Wireguard & NAT (router01)

We specify a single peer on router02 for reasons of routing and configuration

sanity; we want to treat all connections coming from any of

workstation01, backup01, or router01 as if they were coming straight

from router01, and we want router01 to appear as just another ordinary

host on the 10.10.0.0/16 Hetzner private network. Unsurprisingly,

we achieve this by performing NAT on router01. router01 is running BSD

with pf, and so a pf rule like this suffices:

nat on $nic_wg1 from $nic_dmz:network to any -> ($nic_wg1)

That should be pretty straightforward to read: Any packet with a source

address matching the network of the NIC connected to the office LAN

(10.20.0.0/16) will have its source address translated to the IP address of

the Wireguard interface (10.10.100.1). The address 10.10.100.1 is

deliberately chosen to be one that we know won't conflict with anything we have

defined in the Hetzner private network.

We then use a Wireguard configuration on router01 that looks like this:

[Interface] PrivateKey = ... [Peer] AllowedIPs = 10.10.0.0/16 Endpoint = router02.io7m.com:51820 PreSharedKey = ... PublicKey = ... PersistentKeepalive = 1

We specify a client configuration that will attempt to connect to

router02.io7m.com. We specify that the allowed IPs are 10.10.0.0/16.

In this context, the AllowedIPs directive indicates that any packets

that are placed onto the Wireguard interface that don't have a destination

address in this range will simply be discarded. Because router01 is a

router, and therefore will forward packets it receives, if either of

workstation01 or backup01 attempt to connect to, say, server01, their

packets will ultimately be sent down the Wireguard network interface prior

to having their source addresses translated to 10.10.100.1 by the pf

NAT rule we configured above.

At this point, any of the machines on the office LAN can try to send packets

to server01, server02, etc, but those packets won't actually get there.

The reason for this is that router02 isn't currently configured to actually

route anything, and so those packets will be dropped.

Routing On router02

The first necessary bit of configuration is to set a sysctl

on router02 to enable IPv4 forwarding:

# sysctl net.ipv4.ip_forward=1

At this point, any of the machines on the office LAN can try to send packets

to server01, server02, etc, but those packets still won't actually get

there. This is an entirely Hetzner-specific problem and/or feature depending

on your point of view, and it took quite a bit of debugging to work out what

was happening. It wouldn't happen on a physical LAN, to my knowledge.

Hetzner IP Security(?)

It seems that there's some kind of anti-spoofing system at work in Hetzner private networks that the above setup will trip. Consider what happens here:

workstation01sends a packetAtoserver01.- Packet

Ahas source address10.20.0.1and destination10.10.0.1. - Packet

Areachesrouter01and undergoes NAT. The source address is transformed to10.10.100.1. - Packet

Agoes through the Wireguard tunnel and emerges onrouter02. router02sees the destination is10.10.0.1and so dutifully forwards the packet toserver01.server01mysteriously never sees packetA.

What I believe is happening is that an anti-spoofing system running somewhere

behind Hetzner's cloud network is (correctly) noting that packet A's source

address of 10.10.100.1 doesn't correspond to anything on the network.

There are no servers defined in Hetzner cloud that have

that address as it's a fiction we've created with NAT to make our Wireguard

configuration less complex. The anti-spoofing system is then silently dropping

the packet as it's obviously malicious.

To correct this, we simply apply a second NAT on router02 such that we

transform packets to appear to be coming directly from router02. The following

nft ruleset suffices:

table ip filter {

chain FORWARD {

type filter hook forward priority filter; policy accept;

iifname "wg0" oifname "eth1" accept

iifname "eth1" oifname "wg0" accept

}

}

table ip nat {

chain POSTROUTING {

type nat hook postrouting priority srcnat; policy accept;

ip saddr 10.10.100.1 oifname "eth1" snat to 10.10.0.3

}

}

We set up forwarding between the wg0 (Wireguard) and eth1 (Hetzner private

network) NICs, and we specify a NAT rule so packets with a source address

of 10.10.100.1 are transformed such that they get a source address of

10.10.0.3.

After enabling these rules, workstation01 can send packets to server01

and get responses as expected. From server01's perspective, it is receiving

packets that originated at router02.

It's slightly amusing that we introduce a fictional address on router01 to

simplify the configuration, and then undo that fiction on router02 in order

to satisfy whatever security system Hetzner is using. This is what running out

of IPv4 address space gets us.

Years ago, I had to deal with some

aggravation around IPv6. My connection to my ISP is such that I'm

using PPPoE which means I have to use an MTU of 1492 instead

of the ubiquitous 1500 that everyone else is using:

# ifconfig tun1 tun1: flags=1008051<UP,POINTOPOINT,RUNNING,MULTICAST,LOWER_UP> metric 0 mtu 1492

I'm using Wireguard in various places to link

multiple networks. Wireguard packets have 80 bytes of overhead, so the

virtual interfaces it creates have an MTU of 1420 by default.

You can probably guess where this is going.

On a connection such as mine, a packet of size 1420 plus the 80 bytes of

overhead is 1500. This means we'll run into all of the same problems that

occurred with IPv6 back in 2017, with all of the same symptoms.

The solution? Set an MTU of 1410 on the Wireguard interfaces.

On FreeBSD:

# ifconfig wg0 mtu 1410

On Linux, you can either use an MTU=1410 directive in the Wireguard

configuration file, or:

# ip link set mtu 1410 up dev wg0